For practical quantum computers, extremely low error rates of around or lower are required. That’s about three orders of magnitude smaller than today’s best quantum computers, which have typical gate error rates around . A major challenge is therefore to reduce error rates by identifying, quantifying, and correcting for all sources of error.

Many errors, such as decoherence or gate errors, can be measured directly with experiments. There are, however, so-called “hidden” sources of error that are not directly observable and only appear in the final output state. This makes it difficult to identify which mechanisms are limiting fidelity and to quantify their relative impact. This understandably complicates any attempts to counteract or compensate for them. One such hidden source of error is pulse distortions.

What are pulse distortions?

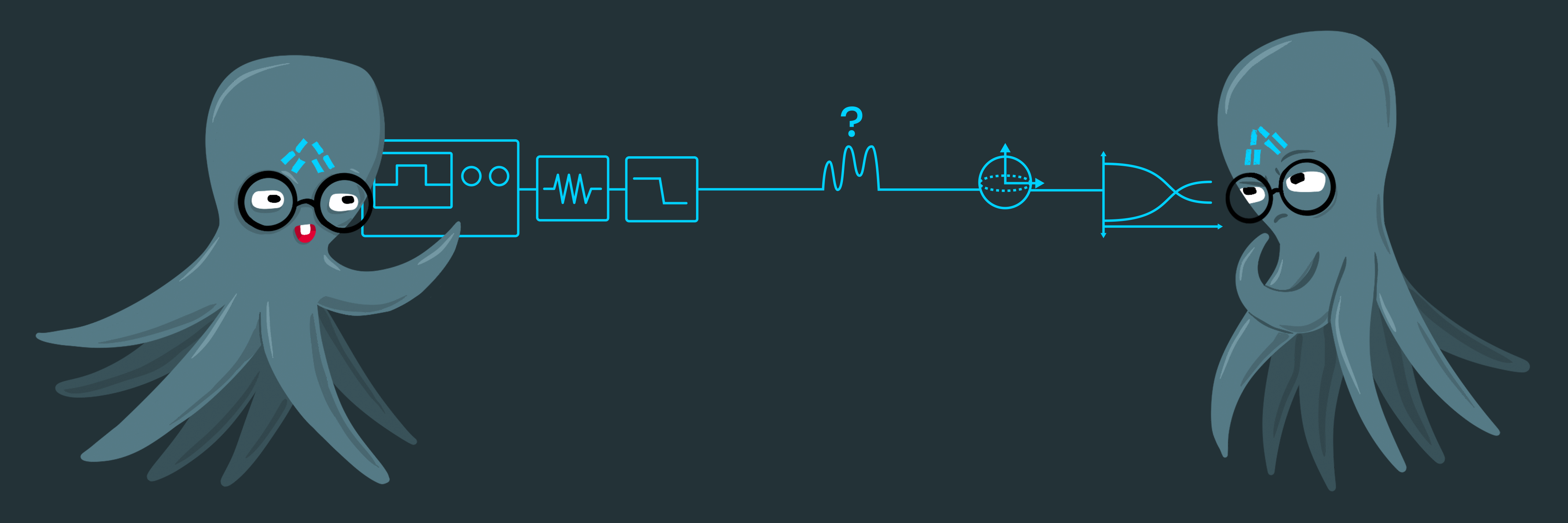

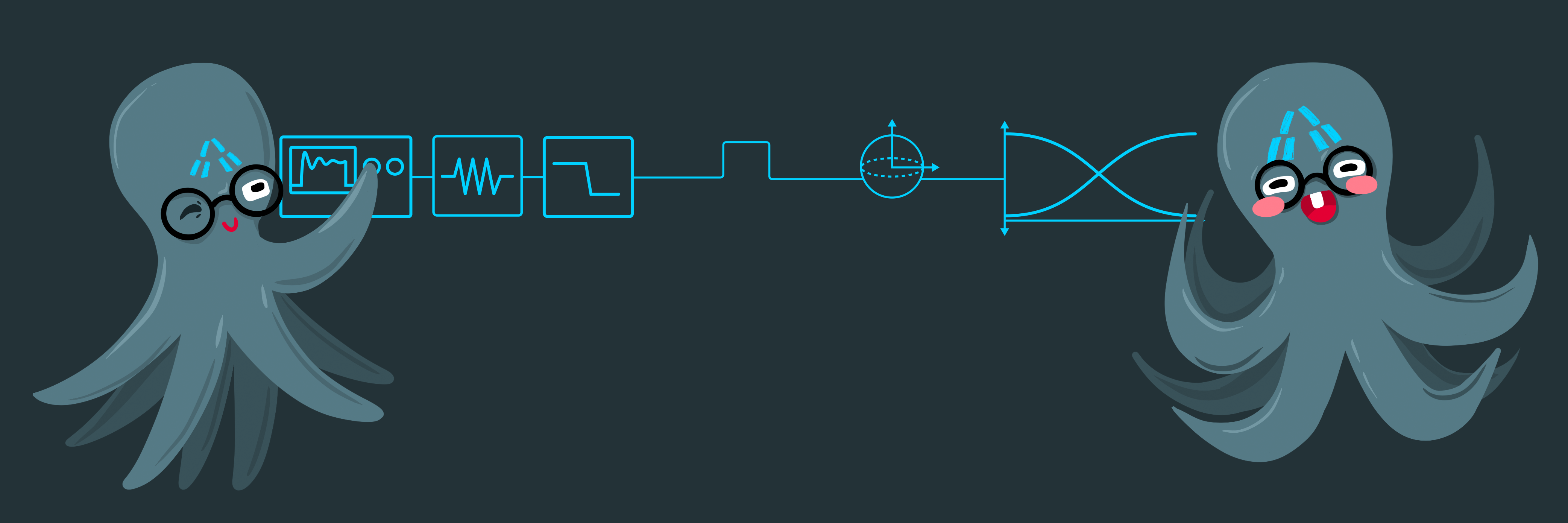

Pulse distortions are unintended changes to the shape, amplitude, or timing of a control pulse between its generation and its arrival at the qubit. They arise because all the elements in the control stack — digital-to-analogue converters (DACs), mixers, filters, attenuators, cables, cryostat wiring, and on-chip components — reshape the pulse to some degree. Bandwidth limits smooth sharp features, impedance mismatches cause reflections and ringing, and non-linearities warp the envelope. As the pulse propagates through the chain, these small effects accumulate, so the pulse arriving at the qubit can differ noticeably from the one programmed in the software.

Crosstalk: Unwanted interactions between neighbouring qubits or control lines arise due to imperfect isolation — a small portion of the drive field leaks into nearby structures, causing unintended rotations if qubit transition frequencies are close.

Control parameter calibration drift: Calibrated parameters drift over time due to temperature variations, bias drift, and component instability, altering the transfer functions of the different control lines.

Timing skew: Signals arriving at different qubits are systematically delayed due to different control line lengths or fixed delays introduced by different electronic components.

Timing jitter: Signals arrive with random shot-to-shot timing delays arising from instabilities and noise in the control hardware.

Why are pulse distortions problematic?

When running gates or gate sequences, pulse distortions introduce systematic, coherent mis-rotations that accumulate across operations. This leads to low fidelities, and, because the distortions cannot be quantified directly, they’re difficult to mitigate. Ultimately, they slow down progress as researchers spend significant additional time calibrating and recalibrating, trying to blindly correct for them. They may spend hours adjusting the pulse amplitude and duration to improve a low gate fidelity, when the real issue is a distortion somewhere else in the control line.

Pulse distortions complicate error mitigation and correction because distortions on different control lines interact through shared hardware and timing, so fixing one path can disrupt another. When pulse distortions vary across the device and drift over time, it becomes harder to build stable gate models, apply decoupling sequences, or fit the noise processes that mitigation and correction techniques rely on.

Scaling to larger numbers of qubits is also made more challenging. As systems grow, control paths become longer and more varied, so each qubit sees a slightly different transfer function, more components are inserted into the chain, and impedance mismatches and reflections accumulate. This leads to greater variation in how nominally identical pulses arrive at different qubits, requiring more demanding individual calibration and still leaving the possibility of residual shaping errors, i.e. imperfect pre-distortion correction.

How are researchers combatting pulse distortions?

There are a number of techniques researchers are employing to reduce the impact of pulse distortions:

Improved hardware design: Better impedance matching, cleaner grounding, and packaging that suppresses unwanted resonances help reduce reflections, ringing, and other distortion-related effects.

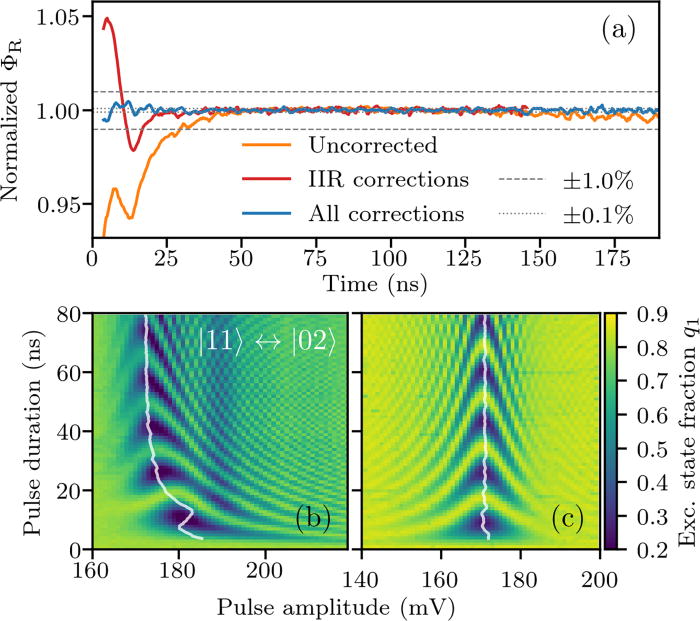

Full characterisation of transfer functions: Measuring the full frequency-dependent response of each control path allows for pre-distortion of pulses so the qubit receives the intended pulse shape. You can see this in action in the plots below.

Automated, closed-loop calibration: Fast optimisation routines continuously tune pulse amplitudes, phases, and shapes to compensate for drift and path-dependent behaviour.

Error-modelling and tomography tools: Techniques such as Hamiltonian learning, gate-set tomography, and cross entropy diagnostics help identify coherent, gate-dependent errors that regular benchmarking hides.

Control schemes robust to small distortions: Composite pulses, derivative-based shaping, and dynamically corrected gates reduce sensitivity to residual imperfections.

Pulse distortions represent a subtle but fundamental obstacle on the path towards fault-tolerant quantum computing. Their hidden, coherent nature means they cannot be addressed by calibration alone, and their influence grows as systems scale in size and complexity. While significant progress in hardware, modelling, and automated control is steadily reducing their impact, pulse distortions must be eliminated completely for practical quantum computation.

Contributors

Kirsty McGhee

Scientific Writer

Albert Hertel

Quantum Physicist