Quantum computers promise to solve problems beyond the reach of even the highest-performing classical computers. For this to become reality, however, processors with far more qubits are required to run useful, fault-tolerant quantum algorithms.

How many qubits are needed?

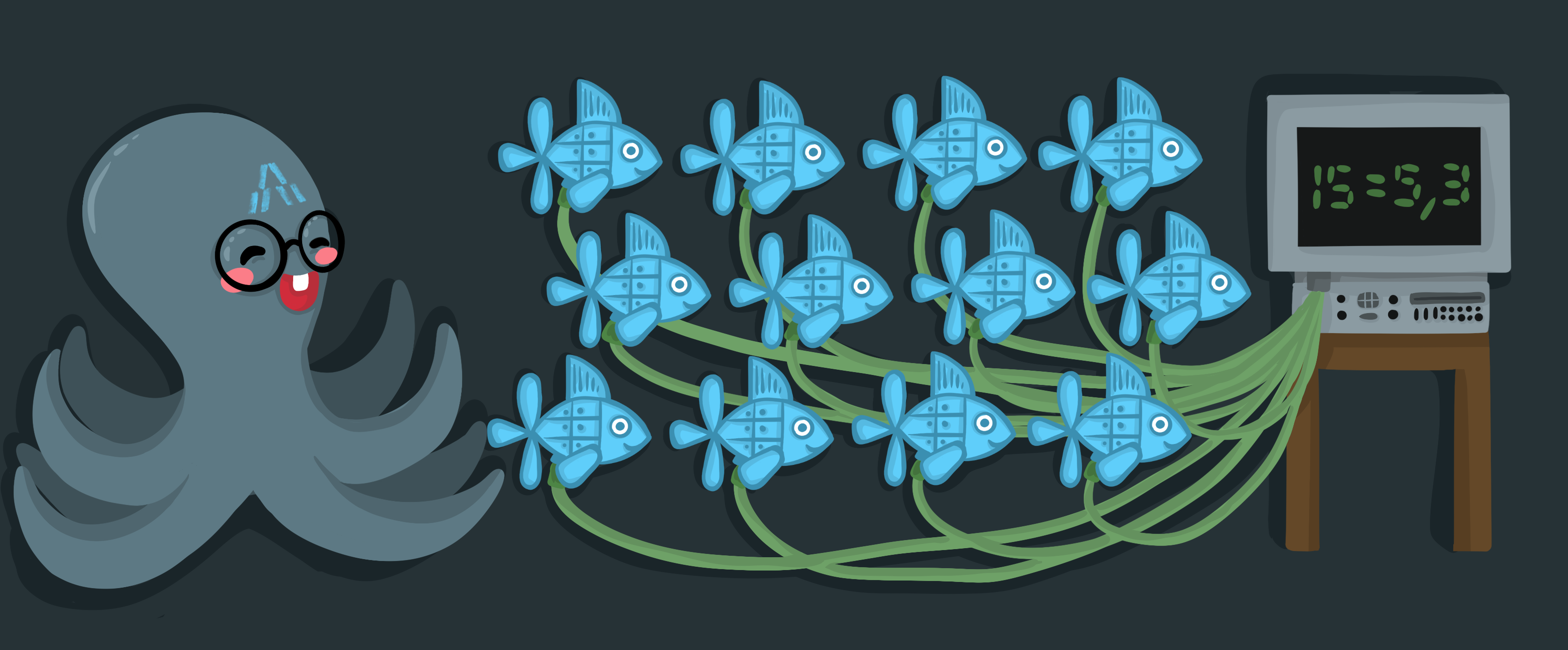

There is no definitive answer to the number of qubits needed for quantum computation: it depends on the problem being solved, the algorithm used to solve it, and the fidelity of the qubits and operations. A well-known example is Shor’s algorithm, which factors large integers into their prime components. For small numbers, classical computers can perform this calculation relatively quickly, but the solve time scales super-polynomially with the number of bits. This makes factoring integers with thousands of bits effectively infeasible.

Shor’s algorithm is significant because it fundamentally changes this scaling, allowing the same problem to be solved in polynomial time — a clear quantum advantage. While it has been demonstrated for very small numbers, such as 15 and 21, these examples are far from large enough to show a meaningful advantage.

Estimates suggest that factoring a 2048-bit integer using Shor’s algorithm would require thousands of logical qubits, operating with sufficiently low error rates, to support long, coherent computations. Accounting for error correction, this would translate to several million to tens of millions of physical qubits. By comparison, the most advanced quantum processors today contain around 1,100 physical qubits, with error rates orders of magnitude too high for large-scale, fault-tolerant operation.

| Application | Benchmark instance | Logical qubits | Physical qubits (millions) | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Factoring RSA-2048 | Integer factorisation using Shor's | 4,000–6,000 | 10–100 | Gidney & Ekerå (2021) |

| Public-key cryptanalysis (ECC) | 256-bit elliptic-curve discrete logarithm | 2,000–3,000 | 2–13 | Webber et al. (2022), Häner et al. (2020) |

| Quantum chemistry/materials | FeMoco ground-state energy at chemical accuracy | 1,500–6,500 | 1–5 | Lee et al. (2021), Caesura et al. (2025) |

| Quantum chemistry/materials | Cytochrome P450 (one enzyme active site) | 1,000-2,000 | 0.5–5 | Goings et al. (2022) |

Why is scaling the number of qubits so difficult?

Each qubit platform faces its own challenges when it comes to scaling. The core requirements for large-scale, fault-tolerant quantum computation, however, are broadly the same for all architectures:

1. Long coherence times

Qubits need sufficiently long coherence times ( and ) such that quantum information is preserved throughout multi-step algorithms. If coherence is too short, even perfect gates will fail simply because the qubits lose their information mid-computation.

2. Extremely low gate error rates

As quantum systems expand, computations involve more operations across more qubits, causing errors to accumulate throughout the device. To reliably execute long quantum algorithms, error rates must be on the order of or lower per logical operation. Such low error rates can be achieved using quantum error correction, which combines many physical qubits into a smaller number of logical ones; however, for this to be effective, error rates on gates, measurements, and crosstalk must lie below a minimum physical error threshold (). If they’re too high, adding more qubits only increases the overall error rate rather than enabling larger computations.

3. Individual control and stable coupling

As qubit numbers grow, it becomes increasingly difficult to ensure that each qubit can be individually controlled without unwanted interactions between qubits and control lines, such as residual coupling and crosstalk. At the same time, intended interactions between qubits must be precisely controllable and stable to enable reliable entangling gates across large networks.

As systems scale, the rapid growth in the number of control parameters makes calibration and long-term stability increasingly difficult. Taken together, these requirements mean that increasing qubit numbers alone does not lead to more powerful quantum computers. Instead, significant advances in architecture, control, and error correction are required before truly practical quantum algorithms can be implemented.

How are researchers tackling this?

To overcome these challenges, researchers are focusing on optimising design and fabrication at both the individual qubit level and the full QPU level.

1. Extending coherence times

For all qubit platforms, this generally involves reducing decoherence through improved qubit design and isolation from environmental noise such as electric, magnetic, and thermal fluctuations. In solid-state systems (superconducting, spin, NV centre, and photonic qubits), this is strongly influenced by materials quality and fabrication, whereas atomic platforms achieve long coherence through low-loss optics, ultra-high vacuum, and intrinsically well-isolated quantum states.

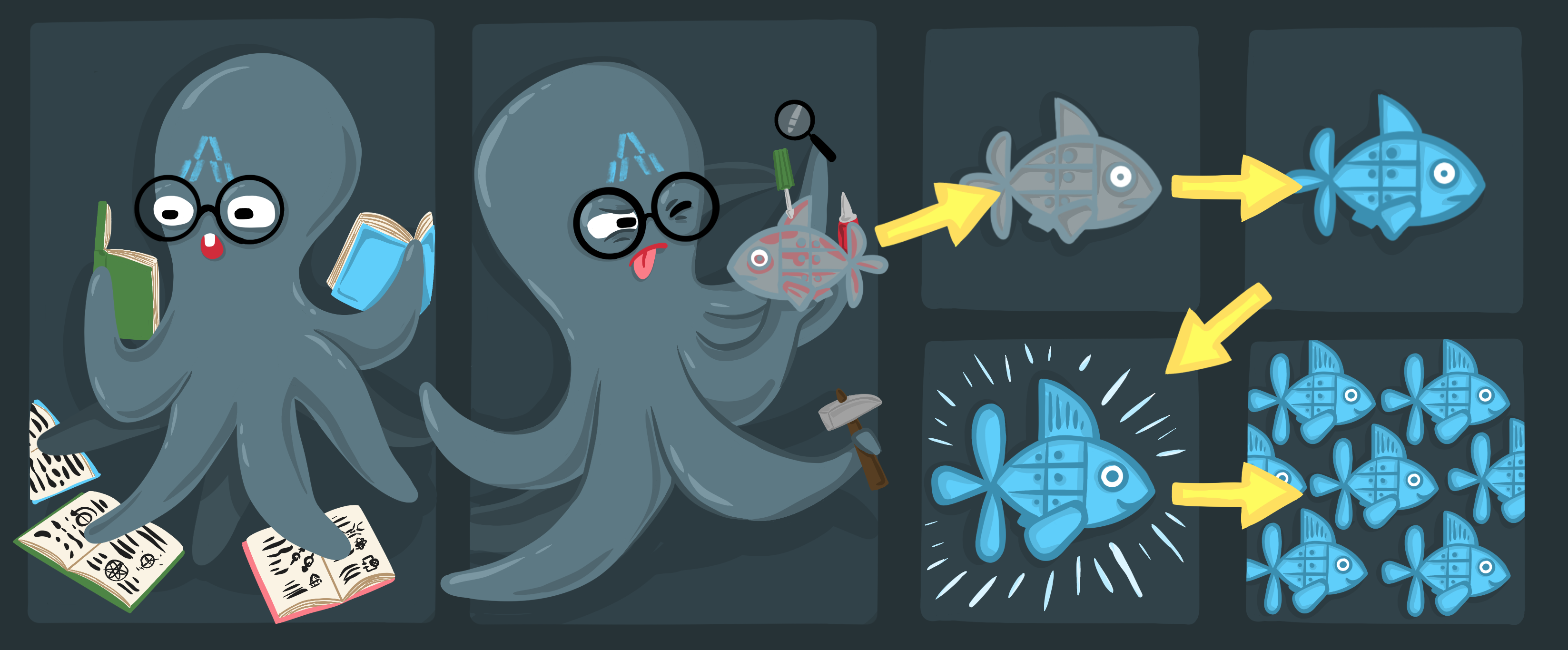

2. Reducing errors

To bring physical error rates to an acceptable level, current research focuses on optimising qubit control, measurement, and system stability. Advances in calibration, pulse shaping, and control electronics reduce coherent gate errors and drift, while improved readout techniques lower measurement errors and unwanted disturbance of nearby qubits. At the same time, quantum error-correcting codes that actively detect and correct errors are being developed and implemented, allowing reliable logical computation even when individual physical operations remain imperfect.

3. Developing scalable control and coupling architectures

Maintaining precise control as qubit numbers grow requires new architectural approaches that scale beyond small devices. That is to say, it’s not just about extending qubit arrays, but reimagining them. Techniques such as multiplexed control and readout reduce wiring and control overhead, while tunable and well-isolated coupling mechanisms enable stable, high-fidelity entangling gates across large qubit arrays.

While researchers are making solid progress in scaling, there’s still a long way to go before quantum computers show a real and significant advantage over classical computers. Making this a reality will likely require fundamentally new approaches and architectures, supported by steady progress in hardware, software, and control techniques.

Contributors

Kirsty McGhee

Scientific Writer